While Zen Buddhism began to have a powerful artistic and cultural influence in America in the last half of the nineteenth century, the Buddhist-Christian dialogue officially began with the Parliament of the World Religions in Chicago in 1896. Buddhist teachers from around the world shared their scripture, their vision, and their spiritual practice with people of other faiths. Some friendships were made, but America’s brief exposure to Buddhism at the Parliament did not result in a flood of new books about ecumenism, and certainly did not cause any of the major Christian denominations to re-examine their beliefs or religious practices based on their contact with the East.

While Zen Buddhism began to have a powerful artistic and cultural influence in America in the last half of the nineteenth century, the Buddhist-Christian dialogue officially began with the Parliament of the World Religions in Chicago in 1896. Buddhist teachers from around the world shared their scripture, their vision, and their spiritual practice with people of other faiths. Some friendships were made, but America’s brief exposure to Buddhism at the Parliament did not result in a flood of new books about ecumenism, and certainly did not cause any of the major Christian denominations to re-examine their beliefs or religious practices based on their contact with the East.

The next public stage of dialogue occurred in the 1950s, when monks and nuns of the Buddhist and Christian traditions began corresponding, and visiting each other’s monasteries. The first popular book about this mutual exploration was Mysticism, Christian and Buddhist by D.T. Suzuki published in 1957. In his Introduction, Suzuki writes that he had been reading the works of the medieval Dominican friar, Meister Eckhart, for over a half century, but was only now offering the West a glimpse of his long ruminations on the apparent similarities between Eckhart’s mysticism and the Mahayana Buddhist worldview. Also in 1957, the Episcopal Priest Alan Watts helped bring Zen closer to the mainstream with his The Way of Zen. By now the interfaith conversation was inviting American Jews and Christians to reflect on their own spiritual lives in new ways. Soon Buddhist teachers were establishing zendos and sanghas on the east and west coasts of the U.S., ministers and priests were reading Taoist, Hindu and Buddhist texts and admiring the spiritual depth they found, and poets were experimenting with Zen literary forms.

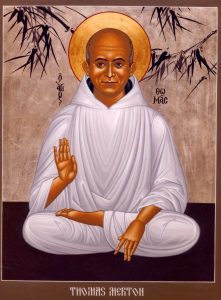

In 1963 the Roman Catholic priest, Dom Aelred Graham, exulting in the fresh winds of ecumenical openness at the Vatican, published his ground-breaking Zen Catholicism. In his Introduction he notes how Pope John XXIII had recently received 28 Japanese Buddhist monks in his library, recognizing their mutual hope for peace, healing and greater compassion among all peoples. Dom Graham’s book, not well known, is a masterful weaving of Catholic, existentialist, Buddhist and literary meanings and metaphors. Graham’s contemporary, the man most widely recognized for bringing Buddhist ideas to the Christian mainstream was the monk and artist, Thomas Merton. A gifted author and spiritual master, his books included Zen and the Birds of Appetite and Mystics and Zen Masters. Merton’s knowledge of the history of contemplative Christianity and his familiarity with the writings of the Desert Fathers such as Evagrius and Cassian, led him to draw rich metaphorical and practical connections between the Biblical tradition of silence before God (“Be still and know that I am God”–Psalm 46), and Buddhist mediation, between Buddhist “emptiness” (sunyata in Pali) and kenosis (the self-emptying of Christ).

The Thomas Merton Society remains an important resource for this continuing conversation.

In post-war Japan two important Buddhist teachers added their unique contributions to American religious culture. Shunryu Suzuki (no relation to D.T.), a Zen master, wrote Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, a sparse and lucid explanation of the Zen way. In a more philosophical vein, Keiji Nishitani, who had founded the Kyoto School of Philosophy, wrote many articles and books that explored Zen in relation to Western philosophers and religion. One of the first influential Tibetan Buddhist writers in America, Chogyam Trungpa, published Meditation in Action in 1969. By the time of his death 1987, Trungpa’s literary output included fourteen books, and he had established Shambhala retreat centers throughout America and Europe.

Academic and practice-oriented Buddhist-Christian conferences began in the 1980’s, and continue to today, sponsored by religious Orders (mostly Roman Catholic), and various universities and retreat centers. Today, it is not uncommon to find Jews and Christians who also have Buddhist practices in Zen, Tibetan or Vipassana traditions. Jews with duel practices have coined the term “JuBu” to designate their unique integrated path. There may be dozens of ordained Christians (mostly in the Roman Catholic tradition) who are also ordained in a Buddhist tradition (usually Korean or Japanese Zen). These would include Fr. Kevin Hunt (Trappist), Fr. Robert E. Kennedy (Jesuit), and Fr. William Johnston (Jesuit). Other well-known Christian monastics and lay teachers who write about their gratitude to Buddhist practices include Ruben Habito, Fr. Laurence Freeman, Sr. Mary Jo Meadow, Fr. Kevin Culligan, Fr. Leo Lefebure, Fr. John Keenan (Episcopal), Beatrice Bruteau, Sr. Elaine MacInnes, Donald Mitchell, and Denise and John Carmody and Dom Aelred Graham. A recent book, Beside Still Waters: Jews, Christians, and the Way of the Buddha, features seven Jews and seven Christians whose lives, beliefs and spiritual practices have been profoundly influenced by their Buddhist meditation experiences. You can read a pdf version of Robert A. Jonas’ essay from this collection, Loving Someone You Can’t See.

More and more books about the Buddhist-Christian dialogue are being published each month. To get the latest sampling, simply “google” or do an Amazon Books search for the phrases “Buddhist-Christian”, “Christian-Buddhist”, “Christian Zen” or “Zen Christian”. (See also Jonas’ Christian-Buddhist Bibliography).

© Robert A. Jonas, 2006-2023 (reprint by written permission only)